What’s the Continuum of Care from Overseas to Arrival in the U.S. for Refugees?

Editor’s note: Last week we hosted a live webinar with PolicyLab researcher Katherine Yun and Minnesota Department of Health’s Refugee Health Coordinator Blain Mamo. The pair discussed how health systems and community organizations can help ensure refugee children and families do not face disparities in health care. The information was so informative, we decided to pull out a section of the discussion that provides key background on the complex care continuum for refugees as they depart from overseas and arrive in the United States. This discussion has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

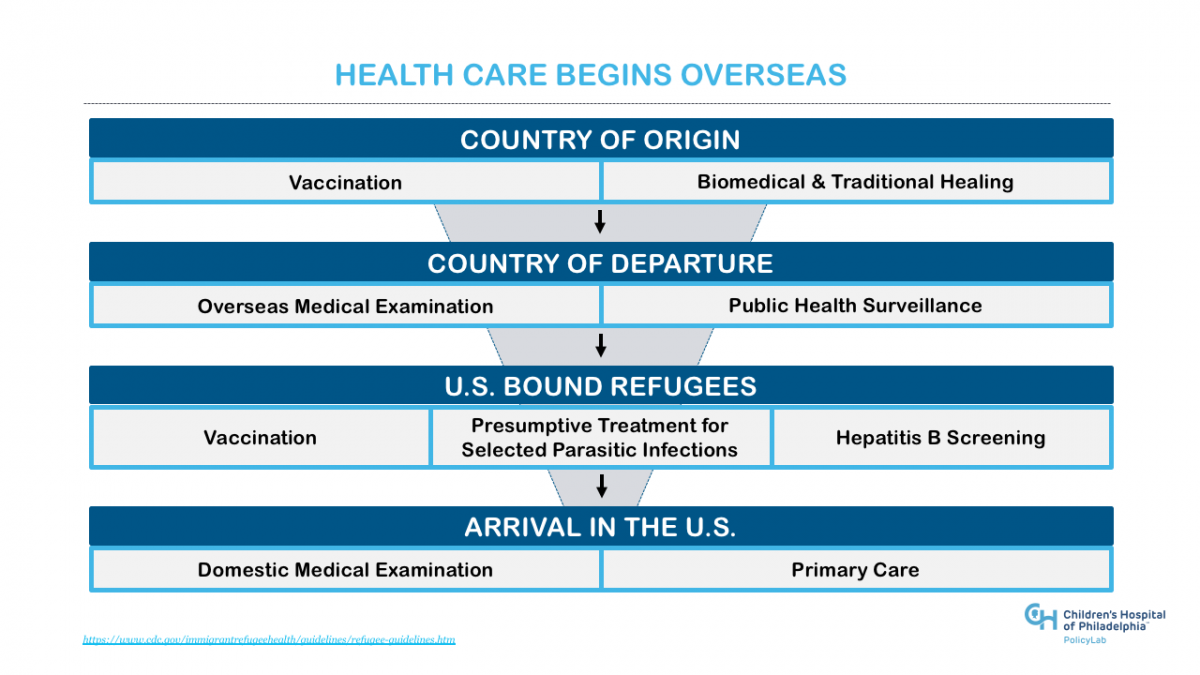

Regardless of where refugees originate from before traveling to the U.S., to promote health and health care we need to consider the continuum of care that begins overseas and may cross multiple borders. It starts with health and public health services provided in the family’s country of origin, includes services overseen by the U.S. government for U.S. bound refugees, and culminates in the Domestic Medical Examination and integration into primary care in the U.S. Below are some highlights of the care continuum from the country of departure to arrival in the U.S. for refugee families.

Country of Departure: Public Health Surveillance

In countries of departure where there are refugee camps or urban refugee populations, there is ongoing public health surveillance. Public health surveillance in the country of departure may be conducted by:

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- National and local public health agencies

- Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs) that provide health services to refugees

- Physicians who conduct the overseas medical examination

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) coordinates with overseas partners to monitor surveillance data for communicable diseases. When surveillance identifies a threat to U.S.-bound refugees, the CDC and partners work to mitigate risk through public health measures to control disease outbreaks. If necessary to reduce the risk of disease importation, refugee departures may even be delayed for individuals and their families until they are no longer at risk. The CDC also communicates with State Refugee Health Coordinators in order to: inform them of overseas outbreaks, identify refugees or refugee groups at risk, describe the steps taken overseas and provide recommendations for domestic follow up if needed.

These recommendations are then shared with U.S.-based health care providers and resettlement agencies at the local level.

Country of Departure: Overseas Medical Examination

Persons with immigrant visas applying for refugee status in the U.S. are required to undergo the overseas medical examination, which includes a physical and mental examination. The purpose of the overseas medical examination is to minimize risk of importing communicable diseases of public health significance. The exam helps to identify the presence or absence of certain disorders that could result in exclusion from the United States under the provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act. The examination is conducted by overseas doctors, called panel physicians, appointed by the U.S. Department of State and guided by the CDC. Currently, diseases of public health significance include tuberculosis, syphilis, gonorrhea, Hansen’s disease, and any disease designated as quarantinable by presidential executive order or as a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization (WHO).

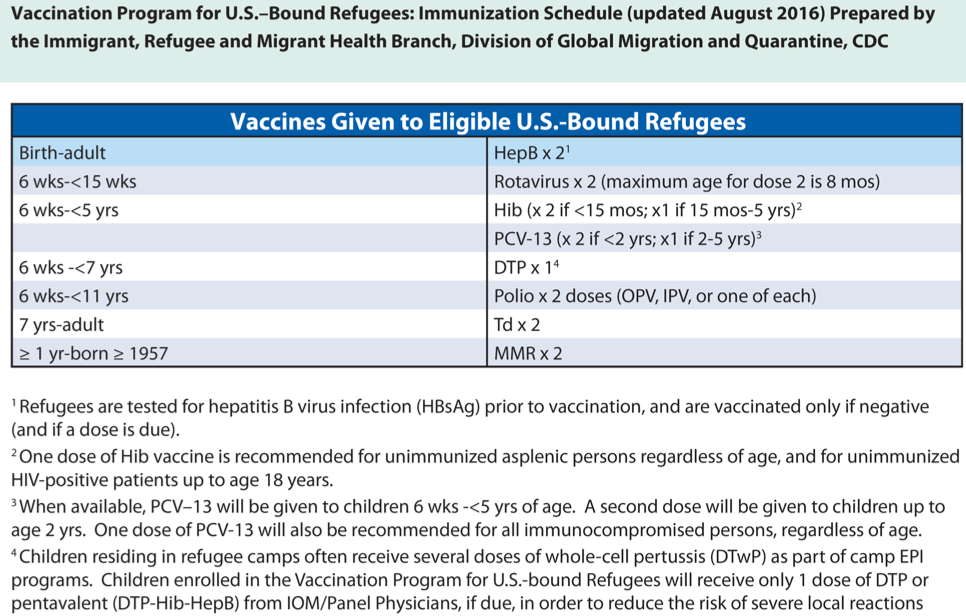

U.S.-Bound Refugees: Vaccination

Additionally, the CDC started implementing an overseas vaccination program for U.S.-bound Refugees in 2012 to protect health, prevent travel delays due to disease outbreaks, and, forchildren, allow more rapid integration into schools after arrival in the United States. This strategy has been shown to be very cost effective. Persons with refugee status are not required to get vaccinations during the overseas exam, however, over 70 percent of refugees entering the U.S. are currently arriving with overseas vaccinations. The goal of overseas vaccination is to provide at least one to two shots of the vaccines listed below.

All valid vaccination records, including documented historical doses and doses provided through the Vaccination Program for U.S.-Bound Refugees, are documented on the overseas medical records received by U.S.-based health departments or health care providers who are encouraged to evaluate and follow-up with necessary vaccinations.

All valid vaccination records, including documented historical doses and doses provided through the Vaccination Program for U.S.-Bound Refugees, are documented on the overseas medical records received by U.S.-based health departments or health care providers who are encouraged to evaluate and follow-up with necessary vaccinations.

U.S.-Bound Refugees: Hepatitis B Screening

As part of the Vaccination Program for U.S.-Bound Refugees, all refugees are offered pre-vaccination testing for Hepatitis B, a viral infection of the liver that can cause liver failure or liver cancer later in life. Overseas testing only includes the Hepatitis B surface antigen, which is a marker for chronic infection. Vaccination and testing help prevent long-term complications.

U.S.-Bound Refugees: Presumptive Treatment for Selected Parasitic Infections

U.S.-bound refugees are also offered presumptive treatment for parasitic infections. These treatments are given shortly before departure to reduce the risk of reinfection. Depending on region, departure country and ethnicity/national origin, refugees may be treated for malaria, schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths including Strongyloides. The treatment schedule is available on the CDC’s Refugee Health Guidelines website.

Arrival in the U.S.: Domestic Medical Exam

Only after completing each of these steps are families ready for travel to the U.S. Once in the U.S., refugees undergo medical screening shortly after arrival through the Domestic Medical Exam (DME). Several sectors are responsible for elements of the DME. Local health departments to arrange the health screening for refugees, as required by their cooperative agreement with the U.S. Department of State. They are also responsible for assisting refugees with their insurance or Refugee Medical Assistance application/enrollment, which provides assistance with logistics, including transportation. Public health systems may work with health care providers and state health departments coordinating the health screening, offering training to providers and assisting with various disease surveillance activities. These are also the primary entities responsible for collecting health screening and disease surveillance data. Health care providers offer culturally and linguistically accessible services, perform complete health screenings and offer referrals and/or follow ups for routine and complex health care needs. Refugees also have access to health insurance, including Refugee Medical Assistance, to ensure they have the means to pay for necessary health screening shortly after children and families arrive in the U.S.

For more on refugee health care in the U.S., be sure to check out our webinar below: